HARRY WAS PLEASED when he got an offer to join a consulting practice in Small Town, USA. On his first day, he arrived with five large boxes full of actuarial books and reference materials in the trunk of his car. Since the boxes were heavy, Harry decided he would carry one box into the office every morning during his first week of work.

Sally, the owner of the firm and the only credentialed actuary on staff, showed Harry around the office and took him to lunch on his first day. During lunch, Sally told Harry that she was hoping to retire in the coming year. “I’m excited about you taking over the practice,” Sally said. “Why don’t you spend your first week familiarizing yourself with the work we’ve done for our current clients. They’ve been with us for many years because we basically do whatever they ask without question.”

Harry was a little startled by that statement, but after lunch he started reviewing files. In the first client file, Harry became concerned with what he saw. There was no documentation for assumptions, and the methodology that was being used was archaic. On his second day of work, Harry brought in another box of books and materials from his trunk and proceeded to review additional client files. This time he found many obvious errors in the work that would have a significant impact on results. Even odder, it was obvious that several of the errors were uncovered by Sally at the time the work was done (because of Sally’s notes in the files), but the final reports didn’t correct for these errors and there was no evidence of any communication to the client regarding them.

Harry was heartened to find one file that had detailed documentation of the development of a 5 percent trend rate— so detailed that Harry could reproduce the trend and conclude it was reasonable. Harry was just starting to feel better about joining the consulting firm when he came across email correspondence in which the client asked Sally to change the trend from 5 percent to 25 percent. Sally’s response had been “sure,” and the final report used 25 percent.

He was torn because while he disliked what he had discovered after only two days on the job, he liked the prospect of taking over for Sally when she retired, and he thought he could clean things up and make the actuarial practice better.

On the third day, Harry decided not to bring another box into the office from his car because he wasn’t sure how long he would be working at the small consulting firm.

For two months, Harry drove around with three boxes in his trunk. During that time, he established models with built-in checks and balances, he encouraged peer review, he documented all assumptions and made sure he was using the most current methodologies, and he continually verified he was complying with all applicable actuarial standards of practice (ASOPs).

Then he asked Sally if he could attend an actuarial meeting to obtain his continuing education credits (CE) for the period.

“I guess that’s fine, as long as you pay for the meeting,” Sally said, adding, “I’ve no idea why you might be interested in attending such a meeting. I haven’t been to an actuarial meeting—or any kind of educational meeting—in 30 years because I think they’re a complete waste of time.”

At the actuarial meeting, Harry attended a session on professionalism that considered a case in which an actuary had knowledge of an apparent material violation of the Code of Professional Conduct by another actuary. At that point Harry knew, despite his efforts to improve office procedures and the actuarial practice, that he needed to have a discussion with Sally to try to resolve what he believed were material violations of the Code. The topics he decided to discuss included the quality of Sally’s work, her apparent noncompliance with ASOPs, his perception that she had failed to adhere to CE requirements even though she regularly issued statements of actuarial opinion, and, ultimately, potential material violations of the Code.

When Harry returned from the actuarial meeting, he asked Sally to meet him at a small corner café. When he told Sally what he wanted to discuss, Sally started breathing very heavily, got red in the face, and after a couple of minutes blurted out, “How dare you question me? I’ve been doing things the same way for the past 30 years, and I don’t need to change a thing. I know everything.”

A Call to the ABCD

Reluctantly, Harry went home with the three boxes in his trunk and contacted the Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline (ABCD). He was reluctant because he thought Sally had taken a chance with him and he owed her something. But he knew calling the ABCD was the right thing to do. In his communication with the ABCD, Harry outlined what he considered to be material violations of the Code. A representative of the ABCD contacted Harry to discuss the matter and obtain a few details that Harry had omitted. When asked whether he had any questions, Harry asked how long the ABCD’s complaint process took.

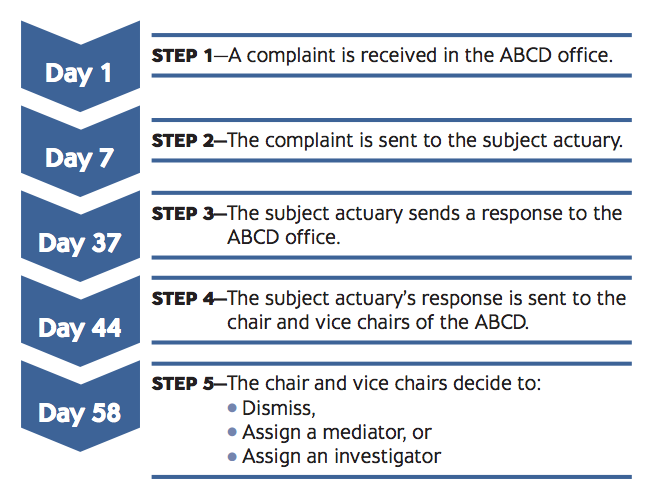

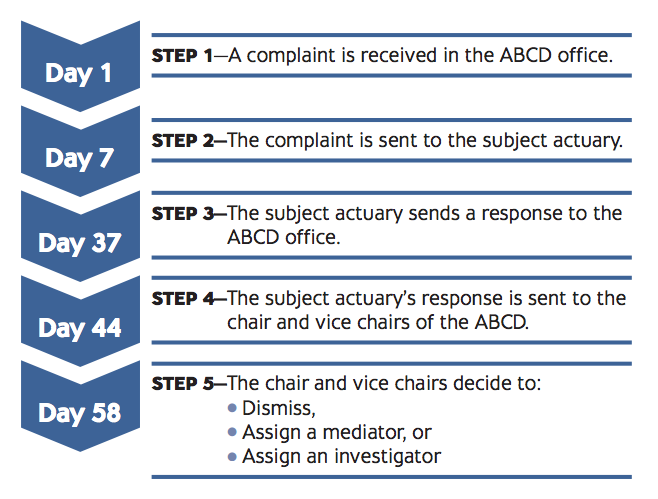

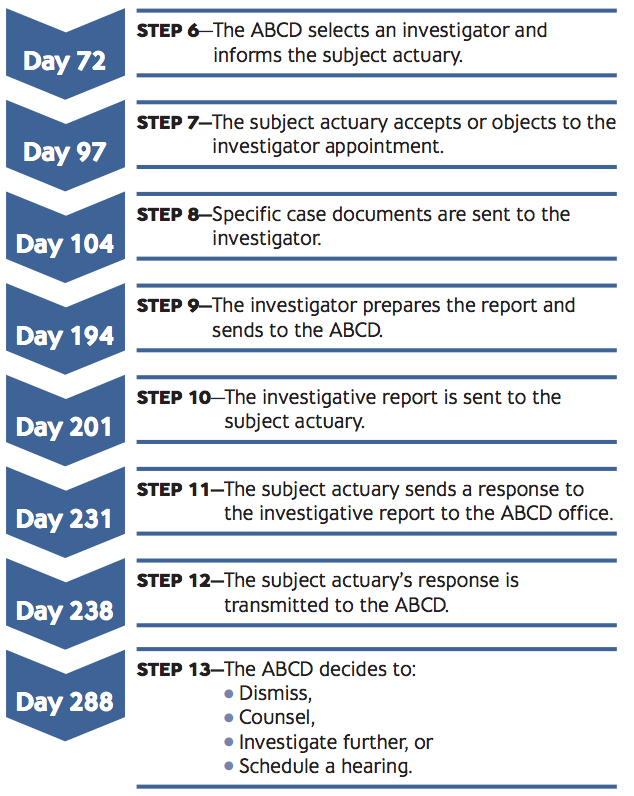

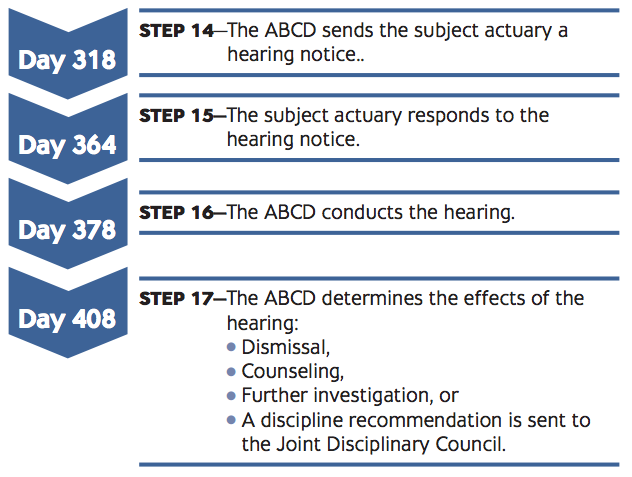

It was a good question. The complaint process is designed to be thorough but is also complex and can be lengthy. The ABCD has an informal guide to time frames that was approved in June 2004. The guide combines ABCD rules that dictate some time frames with target time frames to ensure the process is as rapid as possible. Harry was given the following summary of the informal guide.

In the first step of the process, the chairperson and the vice chairpersons of the ABCD determine how to proceed with a complaint.

Once the chair and vice chairs determine the complaint should be sent to an investigator, the investigator completes a report that is sent to the ABCD and the subject actuary, and the ABCD ultimately determines if a hearing should be scheduled.

If the ABCD opts to schedule a hearing, the ABCD will decide the outcome of the investigation.

The ABCD then will notify the subject actuary and the complainant and, as applicable, either effect counseling or prepare a report with a transcript to send to the subject actuary and the membership organizations.

This is only a target time line. Unforeseen or special circumstances will affect the timing of each case. Examples include:

- Addresses and/or contact information currently on file for the subject actuary that are no longer valid;

- A complaint that covers multiple individuals;

- The subject actuary provides a reasonably satisfactory explanation as to why he or she can’t respond within the scheduled time frame or participate in a hearing as scheduled;

- Circumstances surrounding the case are complex and require an extended investigative process;

- A civil and/or criminal complaint has been filed, litigation has been initiated in state or federal court, sentencing has been delayed, or the case is waiting appeal.

In our hypothetical case, Sally became so distraught that she went to her villa in Barcelona for six months and didn’t tell anyone where she was going. When she returned, she accepted the appointment of an investigator but refused to be interviewed by the investigator or to submit additional requested information despite the investigator’s best efforts. This lengthened the amount of time necessary to complete the investigative report.

Since Sally intended to retire soon, she decided to try and thwart the ABCD from pursuing the complaint against her by resigning her actuarial credentials. Sally quickly discovered that prior to accepting the resignation of any individual’s membership, the actuarial organizations communicate with the ABCD to see if there’s an outstanding complaint against him or her. Resignations may not be accepted by the actuarial organizations if discipline is in progress.

Once Sally received a hearing notice, she asked the ABCD for an extension. “I might want to take a vacation sometime soon,” Sally wrote. “I don’t know if, when, or where I may be going, but if it happens that the best airfare is when the hearing is scheduled, I want to be able to delay the hearing.” The ABCD declined to grant an extension. One week before the hearing, Sally’s father passed away and Sally contacted the ABCD to request an extension, which was granted.

Although Sally’s case is fictional, the circumstances aren’t outrageous when compared with actual cases reviewed by the ABCD. While the ABCD strives to achieve a timely resolution to cases, in Sally’s case the time line exceeded the target. If you are the subject of a complaint to the ABCD, the target time line won’t seem too long. You can shorten it by responding as quickly as possible to Steps 3, 7, 11, and 15. As for Harry, he took a different job and is a very successful actuary. He no longer carries boxes in the trunk of his car.

JANET CARSTENS, a fellow of the Society of Actuaries (SOA) and the Conference of Consulting Actuaries and a member of the Academy, is president, actuary, and consultant with J Carstens Consulting LLC in Minneapolis. She has served on the governing boards of the Academy, the Conference of Consulting Actuaries, and the SOA, and as a member of the Health Committee and General Committee of the Actuarial Standards Board. She is a member of the Actuarial Board for Counseling and Discipline.